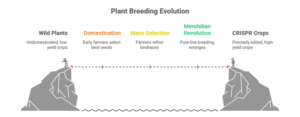

From Wild Grass to Designer Crops

Plant breeding is the oldest biotechnology on Earth.

Long before we had labs, DNA sequences, or even the word “gene”, humans were already rewriting crop genomes — one careful selection at a time.

Here’s the full story, from stone-age farmers to CRISPR pioneers.

Phase 1: Domestication – The First Great Hack (10,000 BCE – 1800s)

Wild teosinte looked nothing like modern maize: tiny ears, rock-hard grains, 5–10 per plant.

Early farmers simply saved seed from the rare plants that didn’t shatter, had bigger ears, and stayed on the cob.

After hundreds of generations → maize as we know it.

Same story with wheat, rice, barley, potato, tomato.

Key tool: Human eyes + conscious selection

Result: Unconscious selection of major domestication genes (e.g., sh1 in maize, non-shattering q in wheat).

Phase 2: Mass Selection & Landrace Refinement (1800s – 1900)

Farmers walked their fields and picked the best-looking plants → “landraces”.

Still no understanding of genetics, but huge gains in uniformity and local adaptation.

Phase 3: The Mendelian Revolution & Pure-Line Breeding (1900 – 1930s)

1900: Mendel rediscovered

1910s–20s: Scientists realize crops are inbred messes

Johannsen develops pure-line theory → breeders start single-plant selection in wheat, oats, soybean

Result: First modern varieties (e.g., Turkey Red wheat derivatives, Marquis wheat)

Phase 4: F1 Hybrid Breeding – The Yield Explosion (1930s – 1980s)

1930s: Hybrid corn invented in the USA

Yield jumped 5–6× in 50 years

Same revolution later hit sorghum, sunflower, rice (1990s), maize in Africa/Asia

Key trick: Inbreed two parents → cross them → heterozygote vigor + uniformity

Downside: Farmers must buy new hybrid seed every year

Phase 5: Green Revolution & Shuttle Breeding (1940s – 1970s)

Norman Borlaug at CIMMYT:

- Semi-dwarf genes (Rht in wheat, sd1 in rice) → short, lodging-resistant plants that respond to fertilizer

- Shuttle breeding between two latitudes → two generations per year

Result: Wheat yield in Mexico went from 750 kg/ha in 1950 to >5 t/ha today

Saved a billion lives. Literally.

Phase 6: Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) – Breeding by DNA (1990s – 2010)

First molecular markers (RFLPs → SSRs → SNPs)

Suddenly you could select for disease resistance, quality, or drought tolerance in seedlings instead of waiting years

Success stories:

- Sub1 gene for flood-tolerant rice (Swarna-Sub1)

- Bacterial blight resistance pyramids in rice

- Quality protein maize (opaque-2 + modifiers)

Phase 7: Genomic Selection (2001 – today)

Instead of chasing individual genes, use 50,000–500,000 genome-wide markers to predict performance

Now standard in commercial maize, wheat, soybean, dairy cattle breeding

Breeding cycle time cut from 7–10 years to 2–3 years in some crops

Phase 8: CRISPR & Gene Editing – The New Era (2013 – now)

For the first time, we can make precise, single-base changes without leaving foreign DNA.

Real CRISPR crops already in farmers’ fields (2025):

- GABA-enriched tomato (Japan, 2021)

- Non-browning banana (Philippines)

- High-oleic soybean oil (Calyxt/Talos, USA)

- Drought-tolerant maize (Corteva, in pipeline)

- Wheat with reduced gluten immunogenicity (Calyxt)

- Rice resistant to bacterial blight via editing susceptibility genes

The Family Tree in One Picture

Era | Main Tool | Precision Level | Time to New Variety | Example Outcome |

Domestication | Human eyes | Random mutations | Centuries | Teosinte → maize |

Pure-line | Phenotypic selection | Low | 8–12 years | Modern open-pollinated wheat |

F1 hybrids | Controlled crosses + inbreeding | Medium | 8–10 years | Hybrid corn yield revolution |

Green Revolution | Induced mutants + shuttle breeding | Medium | 6–8 years | Semi-dwarf rice & wheat |

Marker-assisted | DNA markers + backcrossing | High for few genes | 5–7 years | Sub1 “scuba” rice |

Genomic selection | Genome-wide prediction | Very high | 2–4 years | Modern commercial maize, soybean |

CRISPR/gene editing | Precise base editing | Surgical | 2–4 years (or less) | Non-browning mushrooms, high-GABA tomato |

What Hasn’t Changed in 12,000 Years

- We still need genetic variation to start with

- Selection pressure is still king

- Field testing under real conditions is non-negotiable

- Farmers and consumers decide the final winners

What CRISPR Actually Changes

- Speed: From 10–15 years → 3–5 years (or less)

- Precision: Fix one bad gene without breaking 10 good ones

- Democracy: Small labs and public institutions can now do what only multinationals could before

- Public acceptance: Many gene-edited crops are regulated as conventional (USA, Japan, Brazil, Argentina, Australia…)

The Next 20 Years?

- Stacked traits designed like software (multi-disease resistance + drought + nutrition in one edit)

- De-novo domestication of wild species (groundcherry, orphan millet)

- Climate-proof crops edited for entirely new environments

- Open-source gene editing for smallholder farmers

Plant breeding never stops.

It started with a farmer saving the best seeds under the moonlight.

Today it happens in a lab with a $150,000 gene-editing machine.

Tomorrow it will happen on a laptop designing DNA the way we design apps.

But the goal is the same as it was 12,000 years ago:

More food. Better food. On less land. For more people.

That’s the oldest job in agriculture — and now we’re better at it than ever.

Keep breeding. 🌾🧬

Ready to Finish Your Research Faster?

Offer Ends Tonight—Don't Miss This Opportunity!

Farm Scholars

PHD Success, Guaranteed.

Company

Stay Connected

Follow us on social media for the latest research insights and thesis tips.

© 2025 FarmScholars. All Rights Reserved. | Designed By Ropa Carlos.